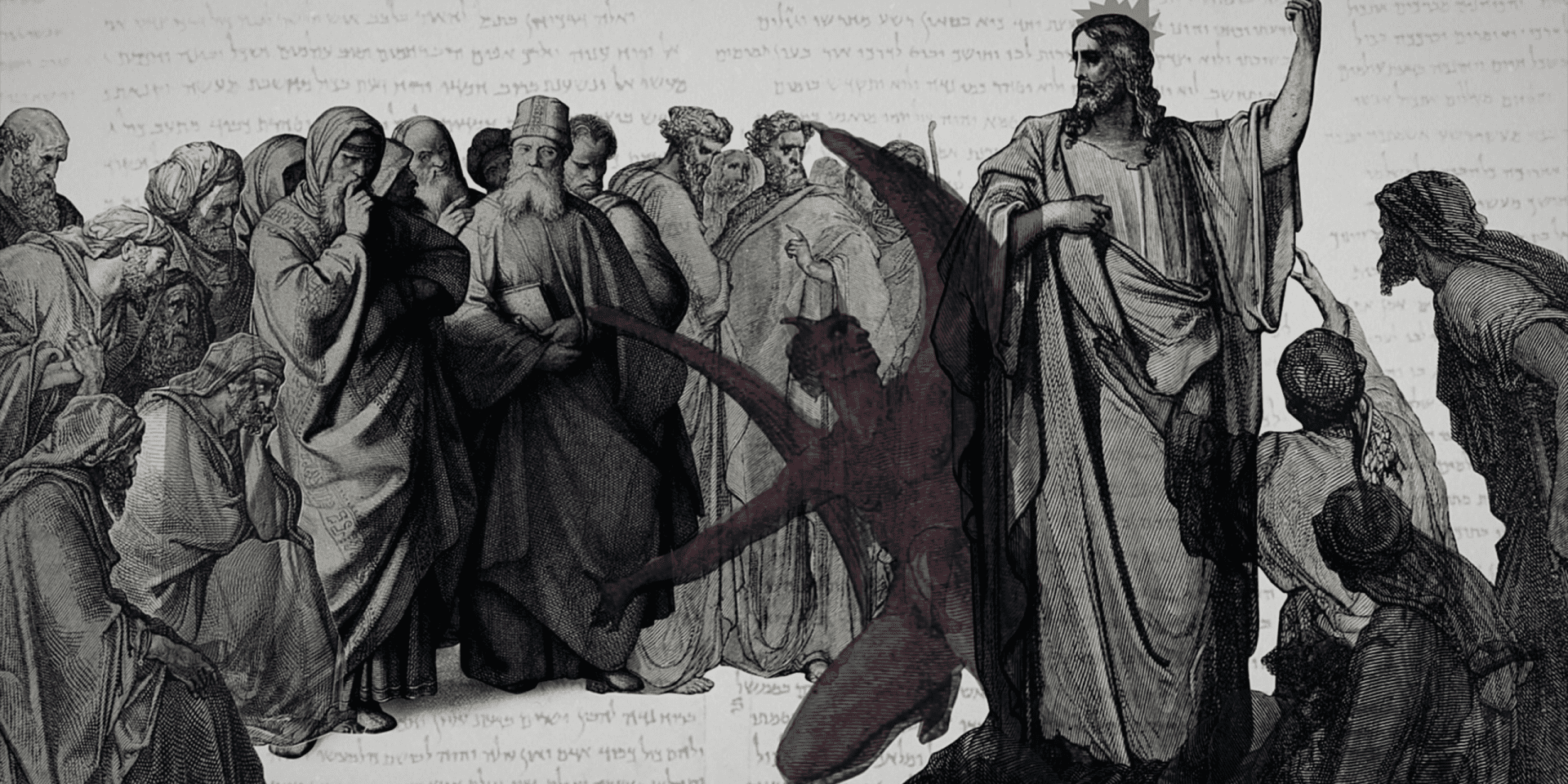

In an incident recorded three different times in the synoptic Gospels (Matthew 12:24; Mark 3:22; Luke 11:15), Jesus is accused of casting out demons by Beelzebul. In all accounts, Beelzebul is said by the accusers of Jesus to be the “prince of the demons”, and even to be in possession of Him. Jesus rejects this claim by pointing out that Satan doesn’t drive out his own team. Satan doesn’t drive out Satan. It was the Pharisees, the religious leaders, who had accused Jesus of operating by the power of Beelzebul as a way of dealing with or countering Jesus’ powers of exorcism.

Another problem existed with their claim though, exorcism wasn’t just practiced by Jesus, some of the Pharisees themselves apparently cast out demons, Jesus said to them, “And if I drive out demons by Beelzebul, by whom do your people drive them out?” (Matthew 12:27a).

“There was a tendency in Judaism to expose foreign gods as demonic imposters”

Today, it is not the strange-to-us accusation of demon possession that bothers readers of the Gospel, but rather the identification of Beelzebul. Who was this entity to these first century Jews?

We know he was seen as an evil spiritual power of sorts, the Prince of the demons, and Jesus seems to equate him with Satan in His defense that, “Satan doesn’t drive out Satan.” But it’s a peculiar fact that in no surviving contemporary sources or Jewish traditions or writings is the name Beelzebul mentioned, though several names for Satan are mentioned.

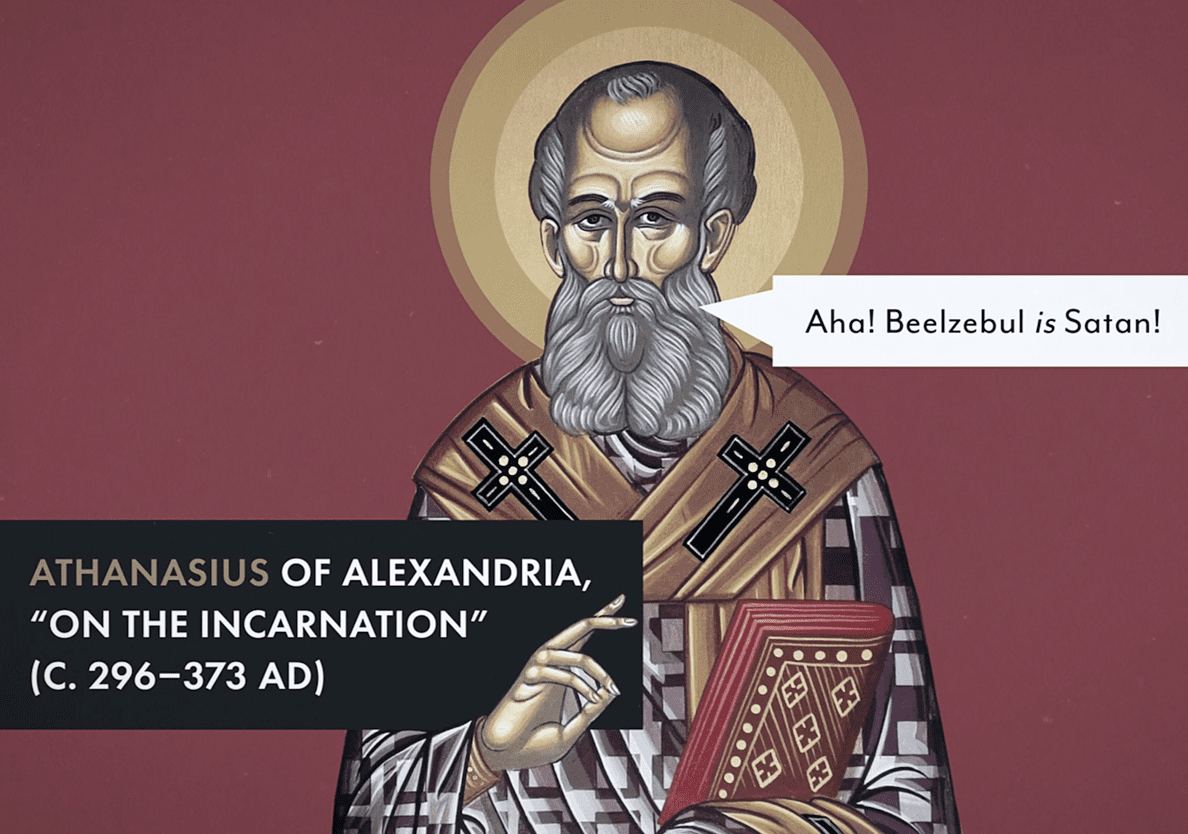

In the fourth century AD, we see Beelzebul being interpreted as another name for Satan based off of Jesus’ quick assertion in verse 26 (Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, in “On the Incarnation”), perhaps, even overlooking the apparent distinction made between the two in verse 27. At any rate, it is still a few hundred years after the fact and doesn’t help us to really understand how Jesus’ original hearers would have understood the term.

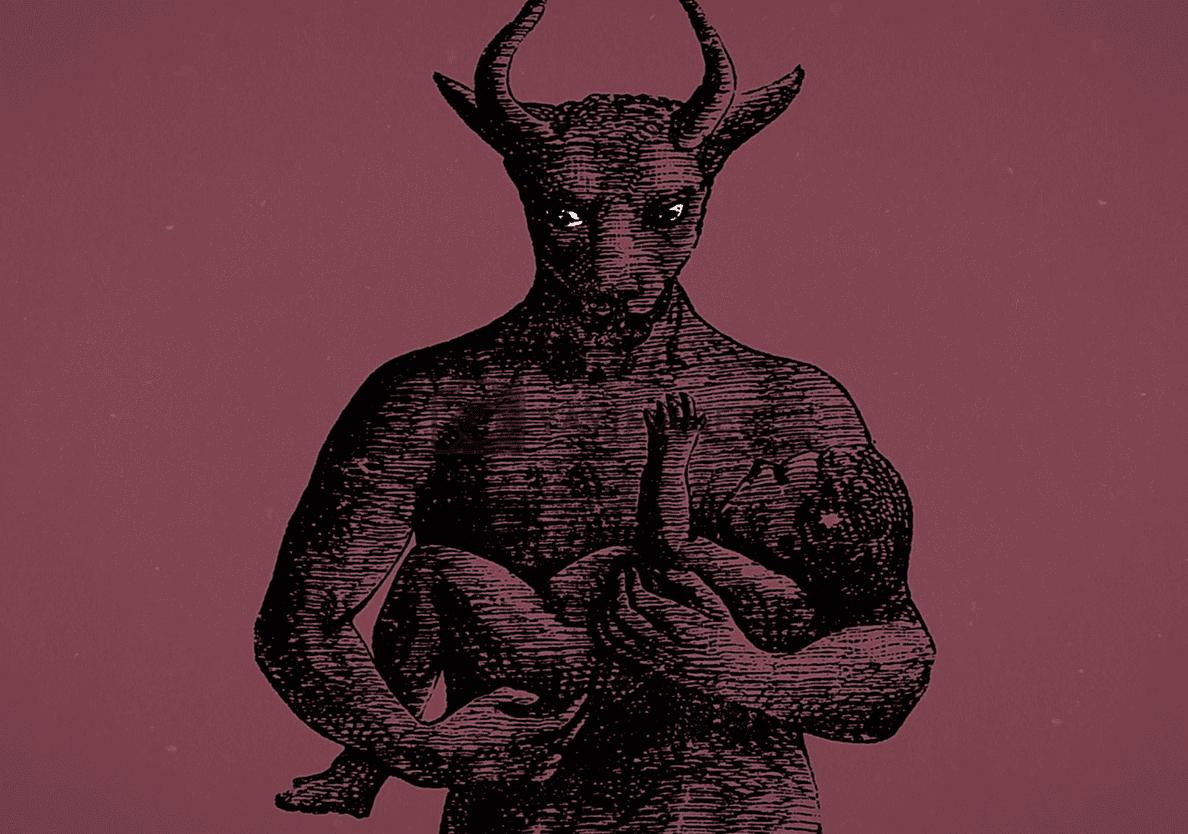

One option is to link this Gospel use of “Beelzebul” with a mention in 2 Kings 1:2 to the Philistinian god of Ekron, “Baalzebub”. In 2 Kings, the ungodly Israelite King Ahaziah, son of Ahab, had injured himself severely and sent messengers to go inquire of this Baalzebub. The Angel of the Lord has the prophet Elijah intercept these messengers and send his message back to the king: Because of his unfaithfulness to God, Ahaziah will die (v.6). The rest of the story includes more messengers of the king dramatically being burned up by heavenly fire.

So, if the Pharisees were alluding to this passage, it certainly would have been a direct way of condemning Jesus. The people were wondering if Jesus was the Son of David, the Messiah in the kingly line (Matthew 12:23). The Pharisees, then, would be saying Jesus is more like the imposter Ahaziah, son of an evil king and pagan queen, whose allegiance lay with the evil god of Ekron. Furthermore, association with this pagan god lead to the fiery deaths of the king’s associates. In other words, Jesus was an evil spiritual imposter, allegiance to whom would lead to the direct judgment of God.

There’s a lot more that can be said about the interesting linguistic changes that seem to have been made from Baalzebub back to its proper name Baalzebul, but for now it is sufficient to know that there was a tendency in Judaism to expose foreign gods as demonic imposters, even changing the spelling, pronunciation, or the meaning of their name to reflect this (homophones). In this case, the writers of the Old Testament changed Baalzebul, meaning “Lord of the High Place (Heavens or Temple)” to Baalzebub, which means “Lord of the Flies” or “Dung”.

Corie Bobechko is a daily co-host, speaker, and writer of Bible Discovery. She also hosts a YouTube channel that shows how history and archaeology prove the Bible. Her heart for seekers and skeptics has led her to seek truth and share it with others. Corie also has a Bachelor of Theology from Canada Christian College.

• Stein, Bradley L. “Who the Devil is Beelzebul?” Bible Review 13.1 (1997): 42–45. https://www.baslibrary.org/bible-review/13/1/13

• Czire Szabolcs. 2018, In: Benyik György (ed.): Hellenistischer und Judaistischer Hintergrund des Neuen Testaments. Szeged: JATE Press 2018. 69-81.

https://www.academia.edu/43671906/The_Beelzebul_Controversy_A_Mediterranean_Cultural_Reading

• Todd Klutz. ‘Beelzebub, Beelzebul. II. New Testament’, pp. 742-43, vol. 3 in Hans-Josef Klauck et al. (eds.), The Encyclopedia of the Bible and Its Reception (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2011).

https://www.academia.edu/36267165/Beelzebub_Beelzebul_II_New_Testament

• “Beelzebul.” Oxford Biblical Studies Online.

http://www.oxfordbiblicalstudies.com/article/opr/t94/e242

• “Beelzebub (Beelzebul, Baalzebub).” BibleGateway.

https://www.biblegateway.com/resources/encyclopedia-of-the-bible/Beelzebub-Beelzebul-Baalzebub

• Kaufman Kohler, “Beelzebub or Beelzebul.” Jewish Encyclopedia.

http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/2732-beelzebub