Before meat suits were fashionable and Gnosticism was the new black, before Baptism was reduced to works righteousness and Communion was trivialized to a game of Simon Says, and long before our world was particles and plastic, the visible world augmented divine intentionality. The physical stuff we universally share and the world we participate in excited, embodied, and revealed cosmic symbols, meaning, and purpose. To the ancients, a symbol was not a bumper sticker we slapped on top of creation, nor was it décor floating aimlessly above reality. Symbols were quite literally baked into the physical world. These symbols were not just verbal, they were visual, aromatic, gustative, textured, substantial. Our world embodied meaning. Meaning was not restricted to our minds. The physical was not at odds with the spiritual, it adorned the spiritual. As the Psalmist says, the physical things pour out speech by day and reveal knowledge by night, it enriches our sense of beauty, wonder, and enchantment; not of God’s mere existence or essence, but of His nature, power, and character (Psalm 19:1-6, Romans 1:18-20). God’s holiness is perceptible in creation.

God created days to set apart one good thing from another, which peaked at God’s final creation made in His image, man and woman. He, then, dedicated and directed the final day of the week toward His holiness for making all things in heaven and earth. God’s holiness manifested a visible hierarchy of symbols from inanimate objects and natural laws to sentient creatures that pointed to Him. God created visuals and rituals: the laws of nature to hold all things, the hydrological cycle for cleansing the waters, the lunar cycle and the daily procession of the sun as well as the days of the week, month, and years for signs and seasons, festivals dedicated to proper worship such as Sabbath, the Lord’s Day, Day of Atonement, and the year of Jubilee. God, then, set apart a nation to be His visible holy priesthood here on earth and commissioned artists, filled with the Holy Spirit, to craft fine articles for the Tabernacle (Exodus 31:1-5), and then Temple, filled with spiritual creatures (i.e., cherubim), prophetic allusions, pleasing aromas, sacred spaces, and holy images reminiscent of Eden. Priests would, then, perform rituals to prophetically foreshadow their future hope and teach the congregation about what it means to be holy. Meaning had visual motion and sensory distinctions depending if it was common or holy, it worked along and through all the physical senses—sight, smell, taste, touch, sound. It was not limited to sound alone, as if faith comes only by speaking/hearing alone (even though it is the primary modus operandi of evangelism and worship, cf. Romans 10:9-11,14-17; 2 Corinthians 4:13-15, 10:5; James 3:1-2). God commissioned sacred art in the form of visuals and rituals to benefit His holy nation. To set the common things apart from the things of God.

To Evangelicals, what does this even mean? What does holiness look like? Smell like? Taste like? Feel like? The Evangelical Church at large, of which I partake, is a disembodied voice, void of physical symbology and visible holiness. Only the invisible counts for something. Barren walls ornament the sanctuary, minimalism marks the pulpit, plastic wrap presents the Lord’s Supper (stuffed with stale wafers and fermenting grape juice), and the chapel’s scent is household. Rather than consecrate and thus elevate a common element to a sacred pedestal, as all things should be given or received in thanksgiving and made holy by the word of God and prayer (1 Timothy 4:5), it is precisely the other way around. Things specially set apart for God are reduced and de-emphasized to common stuff—even our bodies are trivialized. Granted, beautiful hymnals once adorned the halls of our tradition and culture, for which I am abundantly grateful, but even these have long been sanctioned to warm and fuzzy nostalgia and holiday memorabilia. Hymns are no longer sacred art, they are commercialized feelings. We see the outpouring of this thinking in many churches who host rock concerts for Sunday worship service, leading the congregation in cheering rather than raising hands in praise. At first glance they look the same, but they are very different. The secular and sacred have progressively synthesized, steamrolling churches to submission through the industrial conveniences. Even sound—music and sermons—the one sense we had set apart for the Lord’s Day, even more so than the Lord’s Supper, isn’t regarded holy anymore by many. Watch a sermon from your bedroom—it’s the same thing right? It gets the job done. Heck, not even Sunday is sacred, it is just like any other day of the week. You can liken it to cultural happenstance, or you call it for what it is: The sacred is secularized. The holy is common. This was a Christian world. It is no longer.

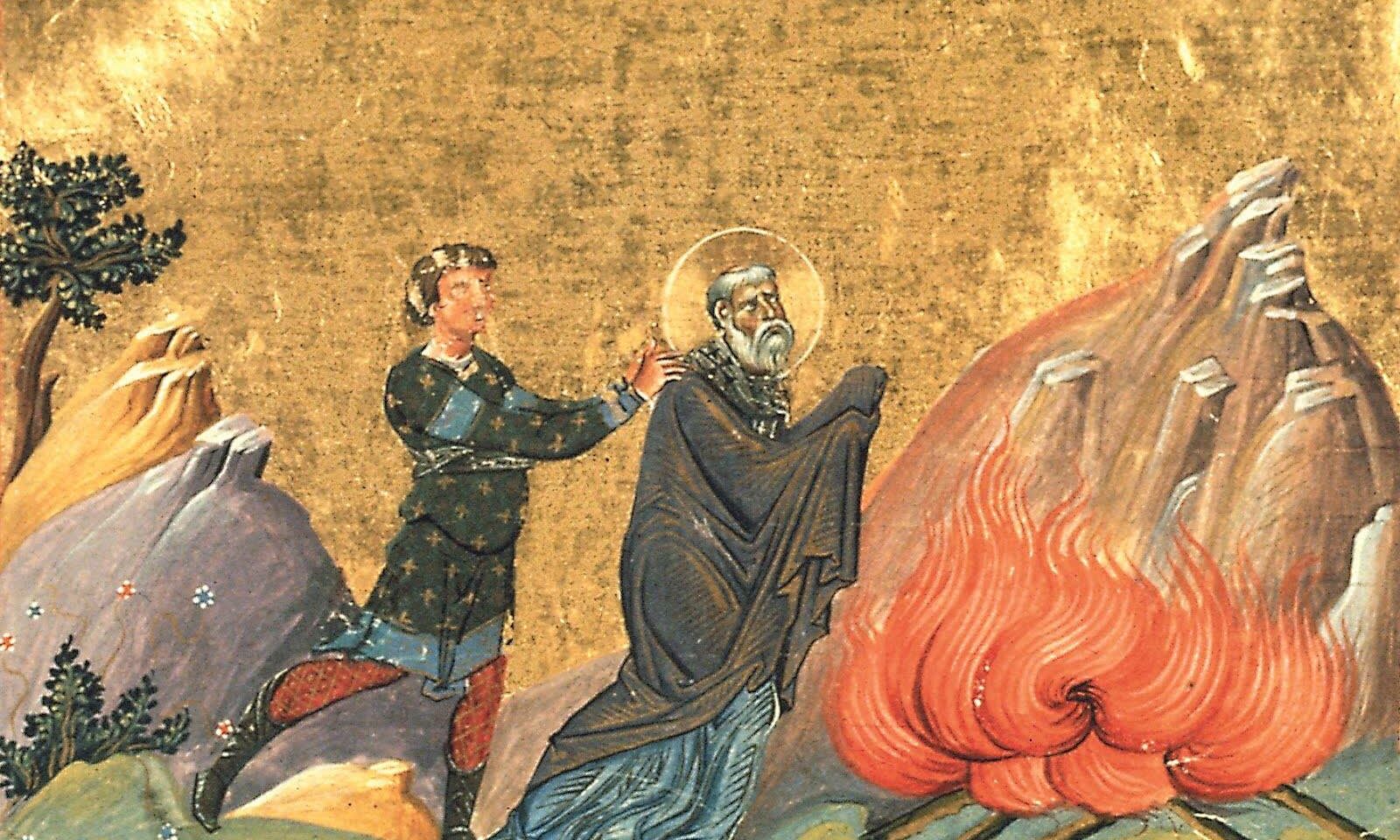

Gone are the days of visible Christian holiness—palpable and palatable it was. Our world is chock-full of superimposed signs, rather than participatory symbols. Consider it for yourself: What is visibly holy nowadays? What is not proverbial? Has industry not streamlined holiness? Communion might as well be served on a conveyor belt. It was prophesied that the nations would offer incense to God (Malachi 1:11). What do you smell in your church? Figurative incense, of course! Granted, we are a fragrance pleasing to God, but this is because we are called to present our bodies as a living sacrifice like Christ (2 Corinthians 2:14-16; 1 Peter 4:1; 1 Thessalonians 5:23). As Paul says, “For it has been granted to you on behalf of Christ not only to believe in him, but also to suffer for him.” (Philippians 1:29) For instance, consider the apostle John’s disciple, Polycarp, the bishop of Smyrna, who was burned alive at the stake for the sake of the gospel, and those who were privileged to witness his martyrdom did not smell burning flesh but sweet spice and frankincense (The Martyrdom of Polycarp, Chapter 15). The symbol of a pleasing aroma actualized as miraculous proof of divine intervention and intentionality. Nowadays symbols are bound to our mental faculties as a product of education and scientific analogies, not the reality themselves. We would first wonder who is baking bread nearby. Yet you cannot have a symbol without their material fruition—you need oil to anoint, bread to eat, wine to drink, water to baptize—you cannot carry out these symbolic rituals with different visual material and, therefore, without the meaning that comes with it.

Further consider the overarching typology of Scripture: We are made in the image of God. We are a symbol. Then God became flesh. The spiritual source became the physical symbol—the visible image of the invisible God. Christ then bodily ascends into heaven as a sign of our future hope, a forerunner of our adoption and glorification. Now, the presence of God—the Holy Spirit, the Spirit of Christ—indwells His visible images. The symbol embodies the symbolized. Our physical bodies were designed to embody God, to participate in God so that God may live through us. God, then, commands us to love Him with our whole being, to present our bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, because we are conforming to the image of Christ (Romans 12:1; 1 Peter 2:5; Colossians 1:15). Our physical bodies are a symbol of the incarnation here on earth and hope to come. We are the holy symbol of God. Seeing the world objectively meaningful and symbolic helps distinguish the holy from the common. But if symbols are not real, then we are figuratively made in the image of God, metaphorically in His likeness, allegorically adopted, analogically glorified. And because of our de-emphasis on full-bodily holiness—sight, sound, taste, smell, touch—we have consequentially become very materialistic. Our once and future bodies are seen materialized rather than glorified, as fleeting dust rather than shining stars, as my own rather than Christ’s (1 Corinthians 6:19-20). Is it not obvious? Idols a perversion of God’s sacred art. Nephilim a counterfeit of the incarnation. Secularism a flattening of sacred hierarchy.

Do not be unequally yoked with unbelievers. For what partnership has righteousness with lawlessness? Or what fellowship has light with darkness? What accord has Christ with Belial? Or what portion does a believer share with an unbeliever? What agreement has the temple of God with idols? For we are the temple of the living God…. Since we have these promises, beloved, let us cleanse ourselves from every defilement of body and spirit, bringing holiness to completion in the fear of God.

– 2 Corinthians 6:14-18, 7:1

Mixing the Holy and the Common

Scripture teaches that there is the common and the holy, and that they ought not to be mixed (Leviticus 10:10-11). It also teaches that sin infects all things. What comes with this infection is the subliminal desire to bring down the holy things to a common level, to make the special normal and the sacred secular, to change gold, silver, and precious stones to wood, hay, and straw, to bring it all to ruin and destroy our sense of special itself, to make worship a thing we created (Ezekiel 44:23; 1 Corinthians 3:12-15). For what? To make God like us, rather than the other way around.

But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his own possession, that you may proclaim the excellencies of him who called you out of darkness into his marvelous light.

– 1 Peter 2:9

If we forbid the visual arts from being sacred, then visual arts can only be secular. If the visual arts can only be secular, then there are spheres in life that do not belong to Christ, individually and corporately. Christian artists cannot produce paintings in holiness like a musician can produce music. How does that make sense? We are called to make the world a sacred space through Christ, to take dominion and restore Eden through faith. If we are commanded to love God with all our heart, soul, strength, mind—in body and in spirit—what does that exclude? That means everything we are and do and have must be sanctified by God through faith. In this, our material expressions in art and ritual cannot be excluded. So to forbid sacred visuals and rituals is to condemn art with secularism, to say it cannot be sacred, it is only common. Perhaps I am wrong or going about this the wrong way, but this seems to strike against our corporate and national vocation to be a holy priesthood if it excludes visual artists.

Do not give dogs what is holy, and do not throw your pearls before pigs, lest they trample them underfoot and turn to attack you.

– Matthew 7:6

Sacred Visuals and Holy Rituals

Here’s what I mean by our overreaction to sacred rituals and visuals. The Sign of the Cross has been used in Christianity for nearly two millennia. It was a common gesture by the time of Tertullian (c. 155-220 AD), and the bishop of Cappadocia, Basil of Caesarea (c. 330-379 AD), later said it originated with the apostles “who taught us to mark with the sign of the cross those who put their hope in the name of the Lord.” (De Spiritu Sancto, Chapter 26) Whether you believe that is true or not is neither here nor there because, truth be told, it is still a Biblical thing to do.

But we reject it. It is even frowned upon. Why?

The Sign of the Cross is a beautiful memorial and faithful expression of our abiding devotion to God. It is traced either on the forehead by a priest/pastor with oil or ash, or you can sign yourself across your torso. In the latter variation, your two fingers and thumb that lead the Sign represent the Holy Trinity—Father, Son, Holy Spirit—and the other two clutched to the palm represent the Incarnation, fully God and fully man, culminating to form the image of the crucifixion over your body. It carries with it the imprint of our vocation, our own cross to bear, our purpose and perseverance in conforming to the image of the invisible God, the daily seal of our hope, our faith, our love, and our ultimate glorification. It is the gospel.

It is also a signature as old as the apostles—why get rid of it?

Are we that unscrupulous, that iconoclastic, that any visual aid or ritual is feared as a rote gesture, talisman, idolatry, or works righteousness? As if our hands moving is a work but our lips moving is not? We speak with our hands, our body, our actions, and at times much louder than our words. We verbally pray blessings over others and ask God to protect us in times of darkness, why not visually? To do-away with such a magisterial visualization of the gospel was to give birth to an idle, androgynous, visionless culture. Or are we too blind to see that? To stuck in our own hindsight to see that we lost foresight, that we have gone too far? Loosened too much? And for what, exactly? Because it is not found in the Bible?! Show me the word Bible in the Bible and I’ll see your point. Or because there’s just no reason to? Well, if you are willing to put our hands in the air when you praise God, willing to kneel on the floor when you pray, lowering yourself before God even though His heavenly throne is not physically in front of you, the Sign of the Cross is another visual expression of the same sentiment. Or is it the slothful response: We just don’t need to? Granted, a lot of things are unnecessary—you for instance—but that doesn’t make it wrong, now does it?

“When, therefore, you sign yourself, think of the purpose of the cross, and quench any anger and all other passions. Consider the price that has been paid for you.”

John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople

But I suspect of all the arguments it is because of its abuses. Now, I understand countering severe abuses, like when Hezekiah destroyed the bronze serpent because the congregation was burning incense and offerings to it (2 Kings 18:1-7), which was a holy relic during the time of Israel, but the Sign of the Cross is not on the same level. Not even close. Consider it: Is the Bible not abused? Is worship music not also? Is the Church building not confused for the Church—should we do away with buildings so that people understand they are the Church? Should we stop playing music? Read a whole book of the Bible for full context of a single passage? Overall, dropping the Sign because of its abuses is just not convincing.

If anything, it is a sign for just how removed we are from physically expressing our faith, and how distant symbols and visuals are in the way we think. To be honest, I think it reveals how our theological understanding of faith and works, believing that “works” pertains to all physical actions in general, has infiltrated our daily lives.

I am also not advocating that there is power in gesturing the Sign mechanistically or insincerely or as a rule, either. That said, I am advocating that it is a valid and powerful form of expressing our faith bodily. That visual gestures are sincere expressions. I think, if we were to integrate it back into Evangelicalism, the Sign of the Cross is a simple way to counteract our anti-symbolic and anti-ritualistic way of thinking. As the archbishop of Constantinople, John Chrysostom (c. 347-407 AD), once said, “When, therefore, you sign yourself, think of the purpose of the cross, and quench any anger and all other passions. Consider the price that has been paid for you.” (Homily 54 on Matthew, 7)

Final Clarifying Thoughts

Our sanctification through Christ produces a way of seeing that which harmonizes God’s prophetic word and spiritual truths with the physical world. This is evidenced in Scripture with symbolic patterns, prophetic imagery, and typological thinking by the authors of the Old and New Testaments, the likes of which offer Godly insight and spiritual fortitude. Holiness is not at the expense of the physical, it is obtained through it by our devotion to Christ, that is by presenting our physical bodies as a living sacrifice.

While the saying is true: “Holy, holy, holy, is the Lord God Almighty, who was and is and is to come!” (Revelation 4:8) That God is a nonmaterial and invisible Being, the holiest of all, we are not invisible beings, and neither is Christ, who bodily ascended to the right hand of the Father. The full deity of God indwells Christ bodily. We are His visible physical creatures, conforming to His likeness, designed to see, smell, taste, touch, and hear. We are made holy by Him. The invisible sanctifies the visible. We were never designed to be invisible, to be void, to be formless. That is why we pray over our food to make it holy (1 Timothy 4:4-5; Matthew 14:19, 26:26; Deuteronomy 8:10). And our bodies in the same way, but even more so. There is a hierarchy of holiness we seem to have forgotten all about.

It would do us well to embrace full-bodily holiness.

Matlock Bobechko is the Chief Operating/Creative Officer of Bible Discovery. He is an eclectic Christian thinker and writer, award-winning screenwriter and short filmmaker. He writes a blog on theology, apologetics, and philosophy called Meet Me at the Oak. He is also an Elder at his local church.