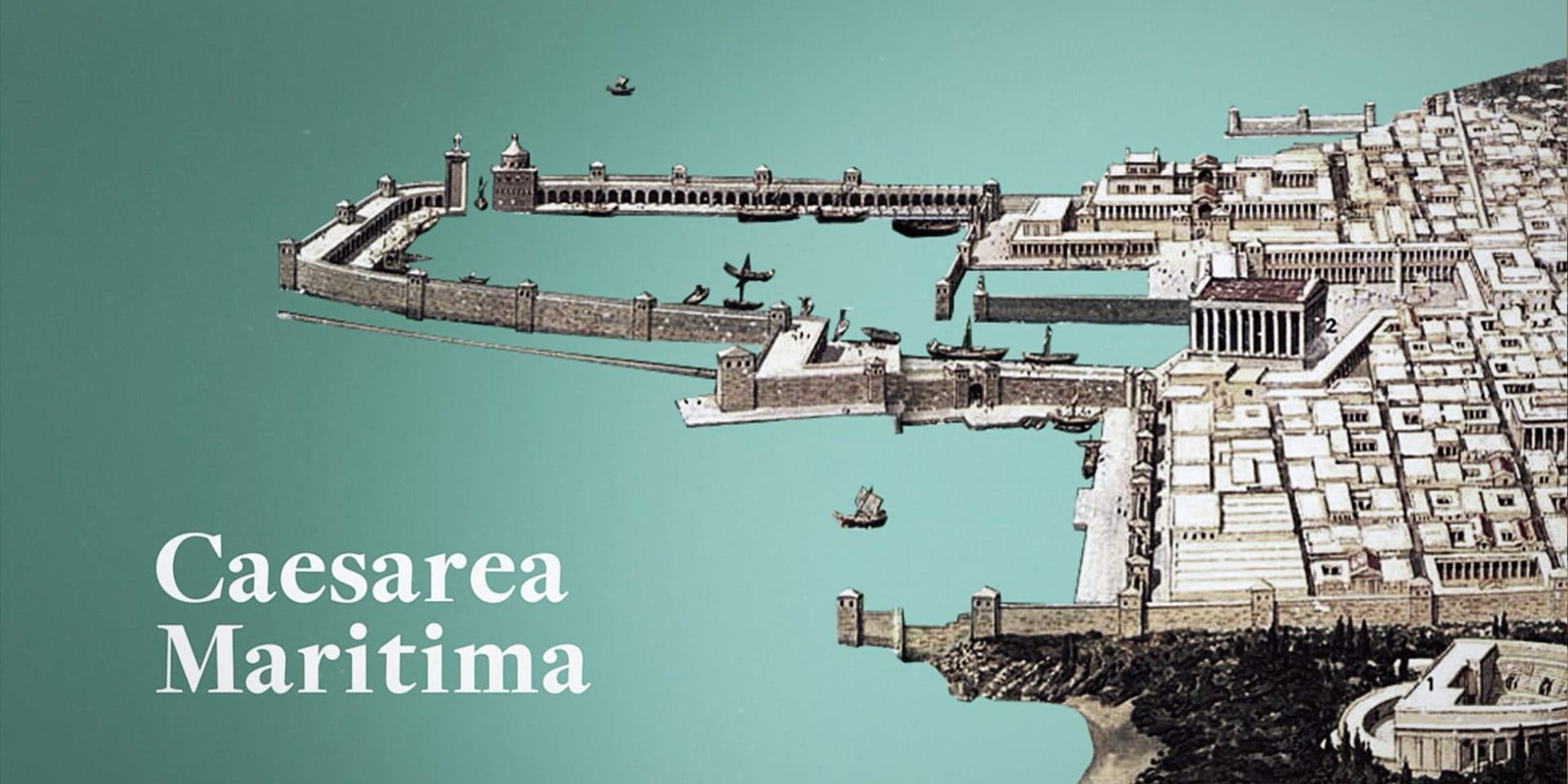

Caesarea Maritima was a grand port city on the Mediterranean Sea built by Herod the Great. It was built on an inhospitable stretch of seashore, overtop of a small, run-down village (Strato’s Tower), and on a scale so large and costly that it took around twelve years to build (22-10 BC).

Herod’s first feat was to construct a massive harbour in an area of sea that was notoriously difficult for sailors having no natural shelter from storms. He did this by constructing two huge stone breakwaters that enclosed a 3½ acre area of sea. The breakwaters extended a third of a mile out into the ocean and were about 200-feet wide so that ships could dock and unload passengers and cargo, and the shorter breakwater even boasted towers. At the sea entrance to his harbour, it’s recorded that Herod erected six colossal statues, three on each side.

The city itself is named after the first proper emperor of Rome, and the man Herod had worked political deals with: Caesar Augustus. And a city named after the emperor and built by Herod the Great had to be illustrious. History records that Herod built the city not with local materials but with expensive and impressive white stone. Fitting to its name, Herod constructed a large Temple to Augustus on a hill of the city, and a massive statue of the emperor to live inside it.

“When they had come to Caesarea and delivered the letter to the governor, they presented Paul also before him.”

Acts 23:33

He built Caesarea’s famous theatre that has been excavated and is still used today, a hippodrome for sporting events and numerous public buildings to support a grand lifestyle for Caesarea’s population. To facilitate a population a sea-flushed sewer system was constructed, along with massive aqueducts that carried fresh water from Mount Carmel to the city. This aqueduct was partially underground and famously, partially above ground. Its beautiful arches are still a major tourist attraction, though as it stands now, the aqueduct was expanded to carry a secondary channel of water built by Emperor Hadrian in the second century AD.

Not to be outdone by the beauty of his city, Herod also constructed a shoreside palace for himself (the promontory palace). Archaeologists have mused about how Herod seems to have enjoyed overcoming nature’s barriers to human construction, and this palace is a good example. Built on a cropping of rock extending into the sea, Herod’s palace had a large freshwater pool at its centre, fed by manmade underground channels. The pool is believed to have had a large statue at its centre, who it would’ve been of is up for debate. The pool was surrounded by walls of pillars to see out into the Mediterranean and with large flower baskets that would’ve made it seem like an oasis. Guests could come and go directly from their boats and the palace was no doubt decorated to inspire awe and wonder at the grandeur of Herod.

After Herod’s death and the creation of Judea as a Roman Province, the procurator or governor of Judea lived at Herod’s palace. Caesarea enjoyed life as the official Roman capital of Judea, a bustling economy, and all of the comforts any ancient city could offer.

Corie Bobechko is a daily co-host, speaker, and writer of Bible Discovery. She also hosts a YouTube channel that shows how history and archaeology prove the Bible. Her heart for seekers and skeptics has led her to seek truth and share it with others. Corie also has a Bachelor of Theology from Canada Christian College.

• Robin Ngo, “New Discoveries Unveiled at Caesarea Maritima: Herod’s ancient port city to undergo major renewal program”. Biblical Archaeology Society. Published on May 04, 2017.

• Robert J. Bull, “Caesarea Maritima: The Search for Herod’s City”. Biblical Archaeology Review 8:3, May/June 1982.

https://www.baslibrary.org/biblical-archaeology-review/8/3/2

• Barbara Burrell, Kathryn L. Gleason, Ehud Netzer, “Uncovering Herod’s Seaside Palace”. Biblical Archaeology Review 19:3, May/June 1993.

https://www.baslibrary.org/biblical-archaeology-review/19/3/7

• Robert L. Hohlfelder, “Caesarea Beneath the Sea”. Biblical Archaeology Review 8:3, May/June 1982.

https://www.baslibrary.org/biblical-archaeology-review/8/3/3