Based off the introduction to his book, the prophet Micah prophesied between 750-686 BC. This makes him contemporary with the Biblical prophets Hosea, who prophesied in Samaria, and the prophet Isaiah, who prophesied in Jerusalem. Micah gave messages from God to the leaders of both of those cities: Samaria, the capital city of Northern Israel, and Jerusalem, the capital city of his nation, Judah.

Not much is known about Micah’s family because he is given a designation of where he was from, rather than whose son he was. The book’s introduction calls him Micah of Moresheth. Moresheth is believed to have been a suburb of the city of Gath, located in Judah’s Shephelah region (lowlands) about a day’s walk from Jerusalem. Micah’s connection to the Shephelah is solidified by his lament for its villages contained in chapter 1.

Micah’s association with Moresheth over and above a family name has led some scholars to speculate that he was an important elder of the people from this region. That he, in a sense, represented them to the ruling authorities especially in Jerusalem, who were the cause of the great suffering that was to come on the people in the form of the Assyrian invasion.

It is also interesting to note that while Micah gave a message to Samaria’s leaders, he chose not to name their kings, dating his ministry only with the names of Jerusalem’s kings: Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah. This could be because Micah saw Samaria’s kings as illegitimate before God, not sanctioned by Him to rule, just as his contemporary prophet Hosea claimed (Hosea 8:4).

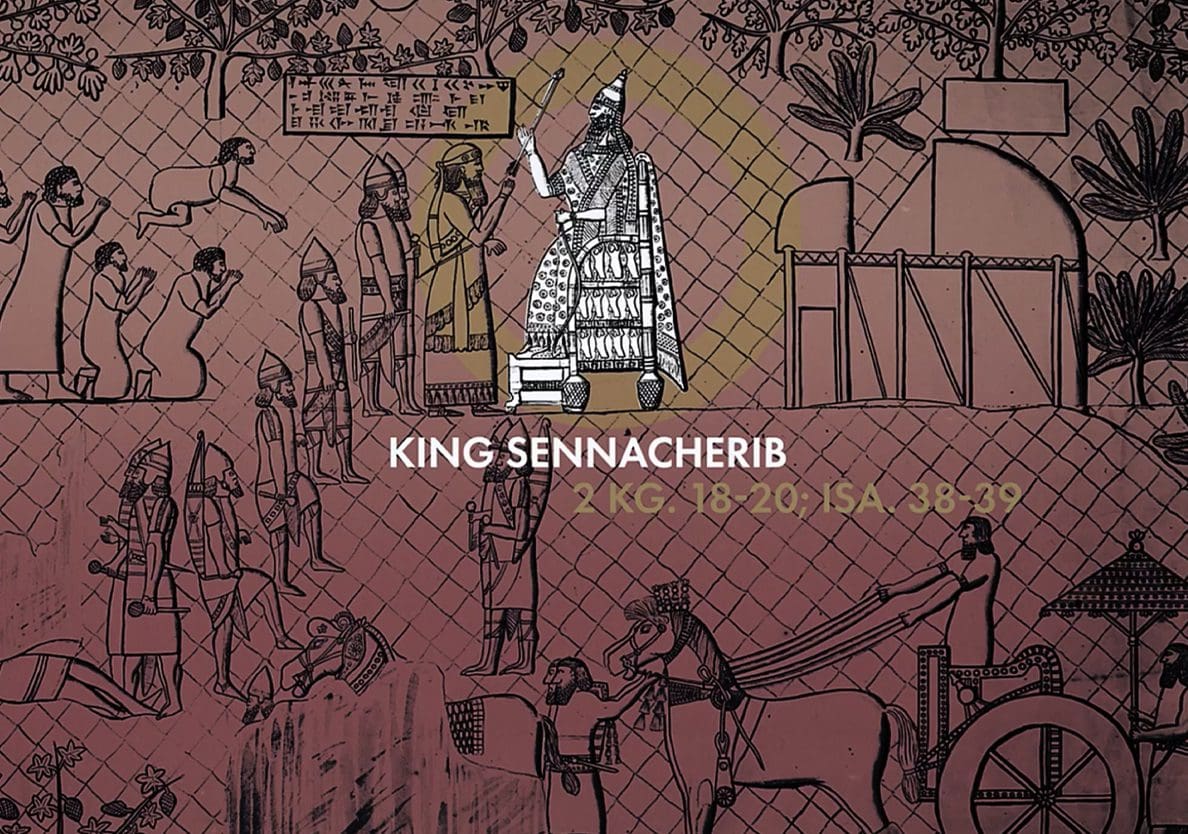

During Micah’s lifetime the main physical threat to Israel and Judah was the Neo-Assyrian Empire. In 733 BC Assyrian King Tiglath-Pileser III took the territories of Gilead and Galilee and deported its inhabitants (2 Kings 15:29). Then in 722 BC Micah’s prophecy of Samaria’s destruction (Mic. 1:1-7) was fulfilled after Assyrian King Shalmaneser V successfully ended a three-year siege of the city (2 Kings 17:5-6), with King Sargon II finishing up the work and implementing additional deportations of Israelites. Finally, Micah’s prophecies of coming destruction on Judah were met when Assyrian King Sennacherib invaded Judah in 701 BC (2 Kg. 18-20; Isa. 38-39), he destroyed all of Judah’s fortified towns and many of its villages, presumably including the ones Micah knew and loved in the Shephelah (Micah 1).

The eventual destruction of Jerusalem itself did not happen during Micah’s lifetime, but sometime later during the life of the prophet Jeremiah. And interestingly, Micah and his prophesies are mentioned in Jeremiah’s book. In Jeremiah 26 (Jer. 26:17-19), elders that were advocating to keep Jeremiah alive, appealed to Micah’s harsh prophecies of Jerusalem’s destruction (Mic. 3:12). Their point was that Micah had prophesied this to King Hezekiah of Jerusalem, and Hezekiah had listened to Micah and repented, rather than tried to have him killed like the king of Jeremiah’s time was attempting. This, the elders claimed, was the reason Jerusalem had been saved.

Additionally, the book of Micah is full of puns, allusions, and word play. For instance, Micah’s name means “who is like the LORD?” and the last section of the book opens with “Who is a God like you?” (Mic. 7:18), which is a clear reference to his name. This unifies the book and shows just how literarily focused Micah truly was, considering that his primary themes were on the covenant fulfillment of Abraham, Moses, David, and all of Israel.

Corie Bobechko is a daily co-host, speaker, and writer of Bible Discovery. She also hosts a YouTube channel that shows how history and archaeology prove the Bible. Her heart for seekers and skeptics has led her to seek truth and share it with others. Corie also has a Bachelor of Theology from Canada Christian College.

How did the prophet Micah of Moresheth die?