One of the weaknesses in the material archaeology of the Biblical world is in recreating the day-to-day lives of the people. Some daily articles made of more perishable materials do not survive in abundance, and without a written explanation of everyday life, it can be difficult to know with certainty how some objects, spaces, and life issues were dealt with.

One of the weak spots in our knowledge is how ancient Israelites dealt with issues of hygiene and sanitation. Living as a human, we all have experiences that allow us to know what concerns the ancients needed to deal with: body odour and general cleanliness, laundry, human and animal waste, dishes, cleaning of the home, and garbage disposal. While our knowledge is not exhaustive, we do get help from the archaeological record.

For issues of personal cleanliness, laundry, and body odour, ancient Israelites had both religious and social motivation. Socially, it is very human that people wanted to mask unpleasant odours, and thanks to written sources we know that perfume, incense, and bundles of aromatic spices were commonly used in all aspects of life to sweeten the air.[1] Israelites also had the added motivation of the Law of Moses that commanded ritual purity, bodily cleansing, and the laundering of clothes after various bodily functions. If they were inclined to follow the Law, then we can safely assume their bodies and clothes met water and a cleaning agent more often than they would have otherwise.

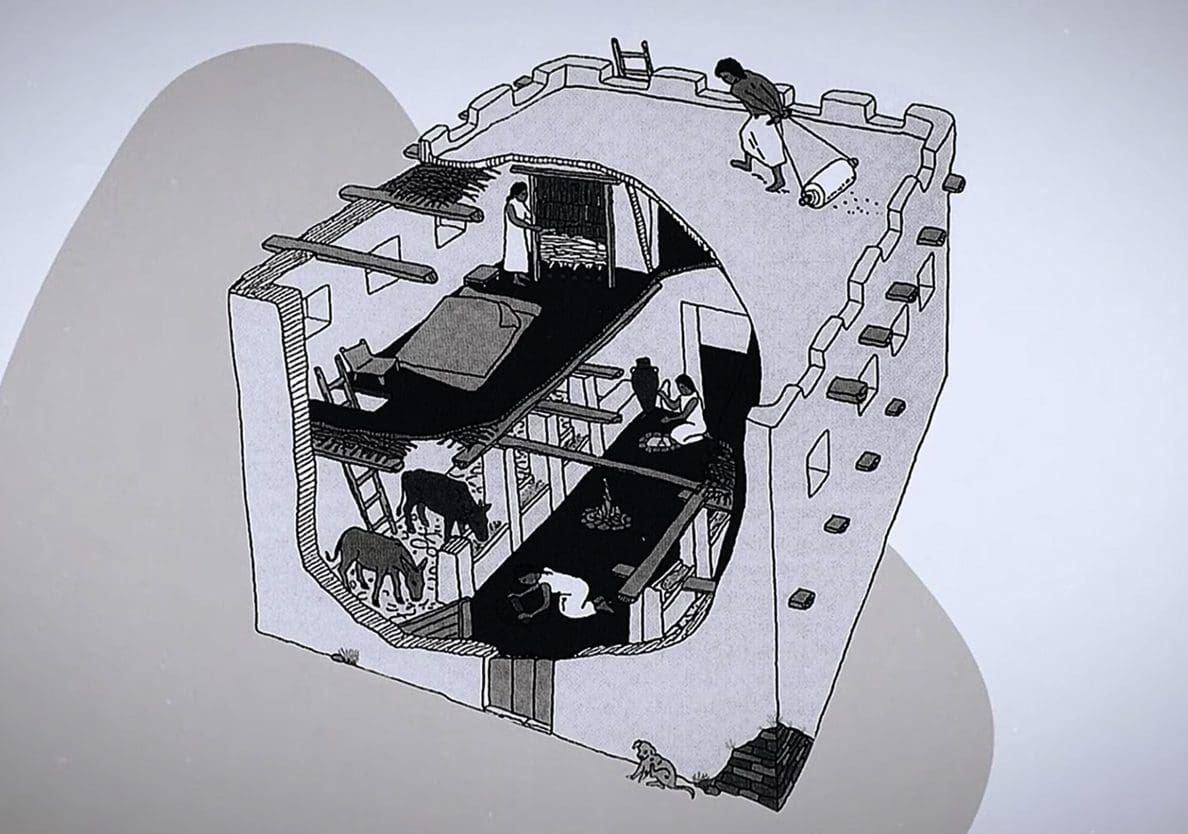

Regarding this ritual purity, scholars studied the four-room house, a style that is bound to the presence of the Israelites in the land and was the predominant floor plan for Israeli homes throughout the time of the Judges and Kings. They have noted that these houses with their central rooms that provide access to all other areas of the house allow not only for greater privacy but also were ideal for observing the ritual purity laws of the Old Testament.

For privacy, a person or visitor did not have to travel through other rooms of the home to reach their destination but could have access to all areas of the house from the central room.[2] The advantage of this arrangement for ritual purity is that members of the household experiencing temporary ritual impurity could move around the house without coming into direct contact with others and also be able to keep up with their daily routines.[3] This is in stark contrast to other societies whose ritual purity laws forced unclean members to live in temporary shelters away from the main home.[4]

While general waste disposal likely varied from city to city several ancient toilet seats have been discovered in excavations.[5] In the city of Jerusalem two of these seats were found still in their ancient place, each over a cesspit.[6] When archaeologists examined the remains of the cesspits, they revealed what a difficult situation ancient Jerusalem must have been in during the days leading up to the Babylonian destruction. And for our interest today, they revealed that liming agents were dumped into the cesspits to facilitate the breakdown and sanitation of these ancient latrines.[7] It is believed that these types of accommodations may have been reserved for the upper classes of society.[8]

Corie Bobechko is a daily co-host, speaker, and writer of Bible Discovery. She also hosts a YouTube channel that shows how history and archaeology prove the Bible. Her heart for seekers and skeptics has led her to seek truth and share it with others. Corie also has a Bachelor of Theology from Canada Christian College.

[1] Nielsen, Kjeld. “Ancient Aromas,” Bible Review 7.3 (1991): 26–28, 30–33.

[2] Faust, Avraham. “Purity and Impurity in Iron Age Israel,” Biblical Archaeology Review 45.2 (2019): 36–43, 60, 62.

[3] Bunimovitz, Shlomo, and Avraham Faust. “Ideology in Stone,” Biblical Archaeology Review 28.4 (2002): 33–37, 39–41.

[4] Faust, Avraham (2019).

Bunimovitz, Shlomo, and Avraham Faust (2002).

[5] Cahill, Jane M., et al. “It Had to Happen,” Biblical Archaeology Review 17.3 (1991): 64–69.

[6] Cahill, Jane M., et al.

[7] Cahill, Jane M., et al.

[8] Cahill, Jane M., et al.

Good article